With the support of the Rita Allen Foundation

Below you’ll find a set of eight comics that @TheCosmicRey produced to complement our book Strategic Science Communication with the generous support of the Rita Allen Foundation. Each strip models a type of conversation we often have when talking about strategy with science communicators. Please feel free to use and share any (or all) of these comics (with appropriate citation, of course).

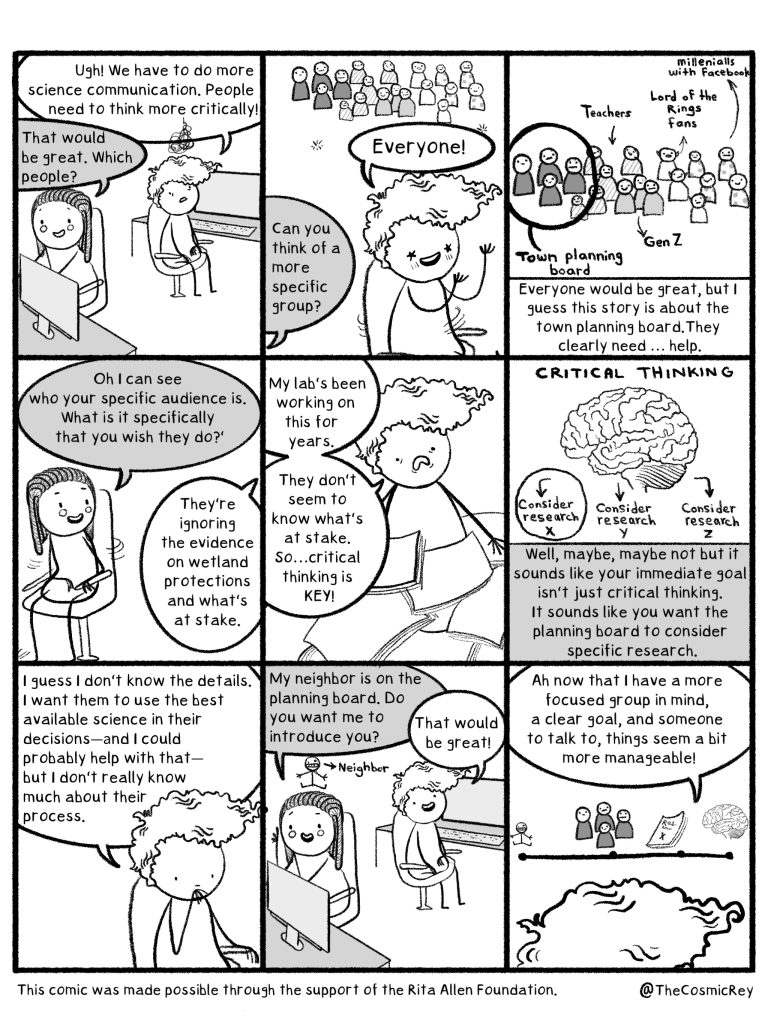

Identifying Audience-Specific Behavioral Goals

This first three comics focus on the challenge of identifying concrete, audience-specific behavioral goals for your communication efforts. This is the focus of chapter 1 of the book and an increasing amount of our research.

In this first one, note the transition from behavioral goal identification to deciding what potential cognitive and affective communication objectives to prioritize.

![[Two people sitting at a table.]

Scientist: I really think people need to feel awe for the universe.

Mentor: Yeah. I mean why do you think so?

Scientist: Why? Because space is awesome. People need to experience that.

Mentor: Yeah, space is pretty awesome but ... um ... WHY should we want people to experience that awe?

Scientist: Awe for awe's sake! Wonder! Joy! Isn't that enough?

[Image of stargazing]

Well ... I remember I used to go stargazing with my mom growing up and one night I got to see a meteor show. It was like the skies opened a glitterbox. That feeling really got me into science.

Mentor: What a beautiful experience. Do you think other kids might have the same experience?

Scientist: Some might. It'll help.

Mentor: So your ultimate goal is to get more kids to choose a science career and your hypothesis is that experiencing awe will help.

Scientist: Yes!

Mentor: That's AWEsome. Given your goal, awe is probably a good place to start but I also wonder what else we might want to communicate to help achieve that goal? Let's keep strategizing ...](http://strategicsciencecommunication.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/RAF-1-768x1024.jpg)

In this second goal-focused comic, note the identification of an audience as well as a more specific behavioral goal. In our research, we’ve found that ‘getting policymakers to consider scientific evidence‘ is typically the behavior that scientists rate as most important.

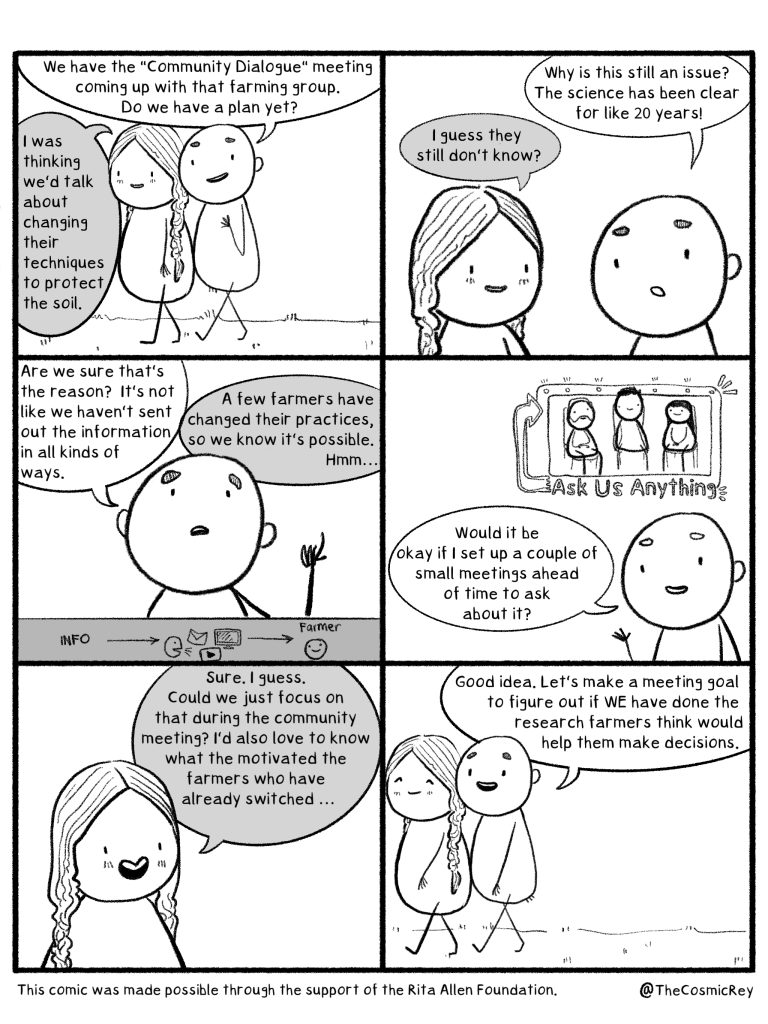

In this third behavioral goal-focused comic, note that the mentor helps the scientist realize that the audience for their behavioral goal is themselves.

An underlying message of the book (and one we’re still trying to figure out how to talk about) is that making the idea of ‘two-way dialogue’ real means setting audience-specific behavioral goals where scientists are trying to use communication to see if they need to change their own research or communication behaviors. In the book, we argue that ‘dialogue’ and ‘listening’ are great, but they’re just tactics.

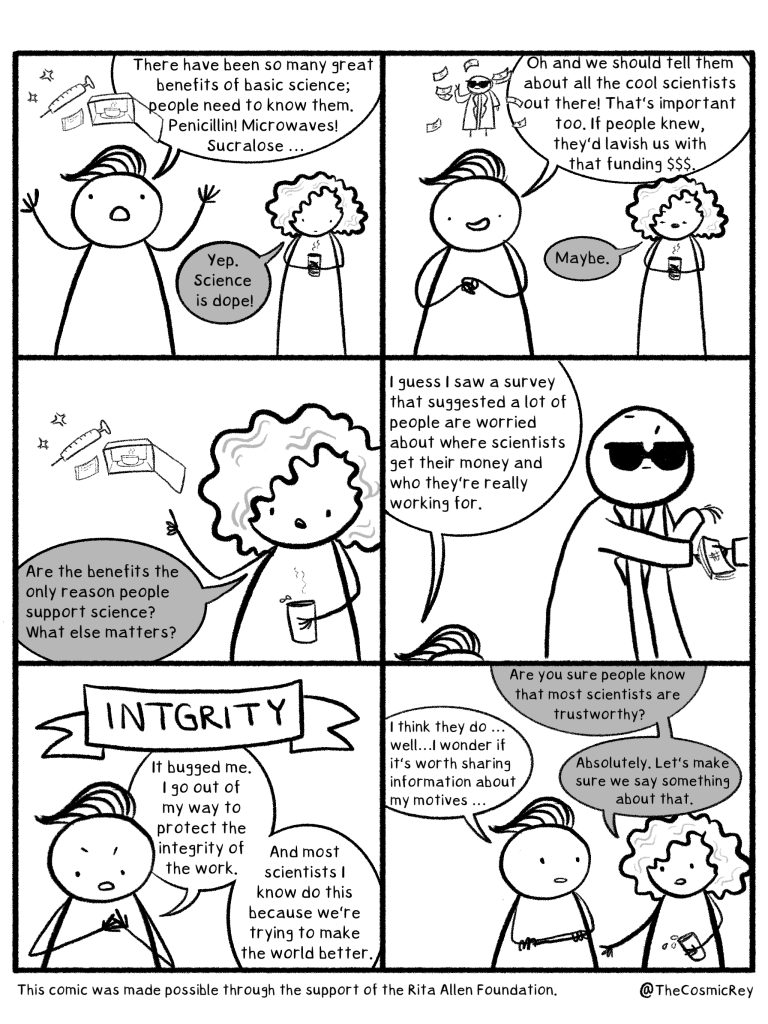

Prioritizing Cognitive and Affective Communication Objectives

Once you’ve identified your goals, you still need to figure out what ‘beliefs, feelings, and frames’ (i.e., BFFs) make it more likely that someone (including scientists) will do the goal behavior.

In this first objectives-focused comic, note that the mentor helps the scientist think beyond just communicating benefits (benefits and risks are discussed in chapter 8 of the book). Specifically, the comic highlights the need to potentially communicate about trustworthiness, especially both integrity (chapter 4) and ‘benevolence’ motivations (chapter 3). Understanding the difference between trustworthy perceptions/beliefs and behavioral trust is important topic of the first section of the book and John’s recent research.

This second objectives-focused comic also focuses on trustworthiness (chapters 2 through 6) but highlights the challenge of ensuring that the scientific community put its best face forward rather than giving in to our frustrations. Our research in this area suggests that being a jerk, probably won’t work (with reference to @ShupeiYuan‘s excellent work).

In this third objectives-focused comic, the focus is on differentiating between content that focuses on risks/benefits (i.e., attitudes, chapter 8), social norms (chapter 9), and self-efficacy (chapter 10). These three types of information and beliefs go by many different names in the literature but underlie most theories of behavior change.

In this fourth objectives-focused strip, we return to the astronomer and her mentor and focus on what types of beliefs/perceptions a scientists might try to communicate once they have identified their goal.

Choosing Tactics

Our last comic calls attention to a central theme of our work; the need to identify our audience-specific behavioral goals and prioritize cognitive and affective objectives before choosing tactics. Unlike most science communication books, tactics aren’t our primary focus.

Of course, our behavior, our message, and our style/tone matter deeply. So too do our choices about source, channel, and timing. But the way we know if we have made smart tactical choices is if they have the effect on our priority cognitive and affective objectives.